graduation party

every firework ember

falling to earth

— John Shiffer (USA)

Published in Modern Haiku, 56:3, Autumn, 2025

Commentary from Hifsa Ashraf:

This haiku captures a bittersweet moment of transition, one that encompasses both endings and new beginnings. The graduation party is a universal milestone, marking a culmination of years of learning, friendships, and youthful freedom. The phrase is straightforward with no punctuation or emotional exaggeration, mirroring the simplicity and shared nature of the experience. It’s a scene most of us can relate to, making it emotionally accessible and real.

The second line acts as a pivot, symbolizing the peak of celebration where fireworks represent excitement, hope, and brilliance. But, there’s a quiet shift as we read “every firework ember/ falling to earth.” The embers, though once radiant, now fall, showing the fleeting nature of youth and celebration. The descent signifies the reality that follows: adulthood, responsibility, and an unknown future.

The closing line, “falling to earth,” deepens the metaphor. It suggests a grounding after a high, a fall not necessarily in failure, but in transition. It’s the movement from a protected world into a vast, unpredictable one. The contrast between the light of the ember and the gravity of its fall is powerful and unique, which lets us reflect on contrasting scenes, suggesting the impermanence and transience of life.

withered flowers

on the temple chariot

morning twilight

— Sathya Venkatesh (India)

Commentary from Jacob D. Salzer:

A powerful haiku that shows impermanence and age-old traditions that have survived over several generations. I see the last line as a metaphor for the mystery of the afterlife. I interpret the morning twilight as a time when our souls continue, long after the physical body (perhaps symbolized by the withered flowers) fades away.

According to Symbolism – Hindu Temple Chariot As Replica Of The Temple by Abhilash Rajendran:

“In many parts of India the sight of a majestic temple chariot rolling slowly through crowded streets is both stirring and sacred. Known as the ratha, these elaborately carved wooden vehicles carry the utsava murti—the processional image of the deity—beyond the temple walls. In effect, the ratha becomes a moving replica of the inner sanctum, bringing the divine presence to every doorstep. This article explores the rich symbolism of the temple chariot, the reasons for its enduring popularity, the profound idea of the god leaving his abode, and many other fascinating facets of this age-old tradition. At its core the ratha is not merely a transport but a microcosm of the temple itself. Every design element echoes architectural features of the permanent shrine: towering pillars reflect temple gopurams, carved panels depict mythic scenes found on sanctum walls, and a miniature vimana (temple tower) crowns the top. When the deity’s image is placed upon this mobile shrine, worshippers are reminded that the chariot is a fully consecrated temple in motion. This replication underlines the belief that the divine resides not only within stone walls but in the very heart of the community.”

I appreciate the notion of seeing the divine in the ordinary. It speaks to a universal compassion that is quite powerful as it transcends our many differences and unites people.

In summary, this is a powerful haiku that sparks deep conversations about age-old spiritual and religious traditions, the impermanence of our brief human lives, the importance of community, and the mystery of the afterlife. Equally important, it shows a kind of compassion that’s universal, revealing divinity or spiritual energy within all people. A beautiful haiku.

protesters marching

wearing

sweatshop shoes

— Michael Battisto (USA)

Published in Modern Haiku 52:1, 2021

Commentary from Nicholas Klacsanzky:

This senryu hinges on irony and ethical tension—a hallmark of the genre’s focus on human behavior. The opening line, protesters marching, shows collectivity and moral purpose. However, as is often the case in senryu, this one ends with a shock of hypocrisy.

The second line, wearing, sets up the suspense for the third line. It is a fine use of enjambment, and the line matches the first line with prominent “e” and “r” sounds to create euphony.

The final line, sweatshop shoes, delivers the punchline—with more euphony. The imagery exposes an uncomfortable contradiction: even with good intentions, we are irrevocably contributing to ubiquitous and exploitative companies. Living in the modern world, we would have to live off the grid to fully rid ourselves of these greedy practices—even with something as simple as shoes. With a masterful stroke, the poet refrains from judgmental language, allowing the irony to speak for itself.

The poem’s emotional effect is quiet but sharp. It provokes self-reflection rather than outrage, as the reader is implicated alongside the protesters. In this way, this senryu eventually centers on empathy. The march continues but with an unresolved weight on its feet.

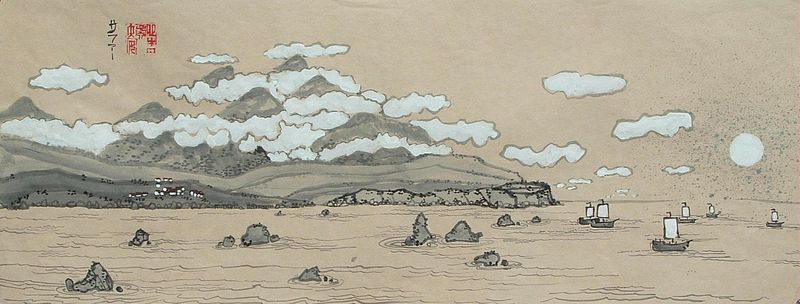

Utagawa Hiroshige I (1797–1858, Japan), Fireworks at Ryogoku (bridge), #98 from the One Hundred Famous Views of Edos eries,1858. Color woodcut print on paper, 14 3/16″ x 9 7/16″ (36 x 24 cm). © 2017 Brooklyn Museum. (BMA-822)